“Whether the Belief that there are such Beings as Witches is so Essential a Part of the Catholic Faith that Obstinacy to maintain the Opposite Opinion manifestly savors of Heresy.”- Malleus Maleficarum

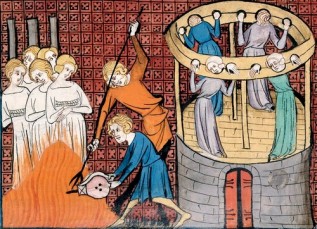

With a decrease in loyal Christian followers across Europe, church leaders sought out way in which to re-establish church hegemony. Across early modern Europe, this manifested itself in ways to seek out the weakest, most vulnerable in society and condemn them witches in order to reinstate Catholicism as the supreme power.

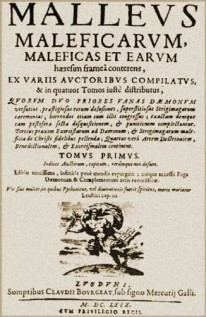

Initially, judges used manuscripts as guidance on how to persecute witches, but these were rare and often varied in content. Alongside the invention of Johannes Gutenberg’s printing press, 1450, the scope and uniformity in prosecuting witches expanded enormously. Manuals were mass-produced and were used by inquisitors to identify, track, prosecute, and kill those suspected of witchcraft.

This invention revolutionised the way knowledge could be circulated. Bibles, flyers and ultimately, demonological literature created an information reformation. The Malleus Maleficarum, (the hammer of the witches) written in 1486 by Heinrich Kramer and Jacob Sprenger is deemed the most influential and notorious book on witchcraft. Looking closer into the nature of the book, it becomes apparent that it is an idiosyncratic text, reflective of the lifetimes of two inquisitors and how their experiences had shaped their beliefs on folklore. These learned beliefs, publicised by the elite, and translated into the main vernacular languages, were able to spread to areas not yet touched by witchcraft and penetrate down through societies. This type of literature became one of the main forces that led witch-hunt continuations, and geographical expansion.

Pope Innocent VIII signed a papal bull, Summis desiderantes affectibus, published in the preface of the Malleus. This papal bull has been acknowledged by many scholars to be the most significant literature issued, and supported by the Church regarding witchcraft. This book was manipulated by religion to spread an air of fear throughout Europe. Wherever this book went, ways to identify, accuse, and condemn a witch followed creating a mad frenzy within communities. Many of the clauses within the Malleus reinforced that even to question simply by virtue the existence of witchcraft as a form of heresy, was heresy itself. Those not deemed pure Christians, or anyone who posed a threat to Christianity became the focus for attack. Societies became deprived of old securities; the resulting panic manifested itself onto witchcraft. As old institutions began to decay, they sought out drastic ways to try and reassert power and authority.

When looking at witchcraft it is easy to make generalisations about the scope, impact and methods for hunting witches. Italy and Spain had considerably lower hunts than other parts of Europe, predominantly because the elite did not accept diabolism. Without elite acceptance, demonological literature did not circulate on mass as it did other areas because there was not a market for it. The Church was the main influence in whether or not witches were to be hunted, and to what extent. The printing press was used as a medium to carry fears about witchcraft, and allowed these ideas to reach a scope never seen before.