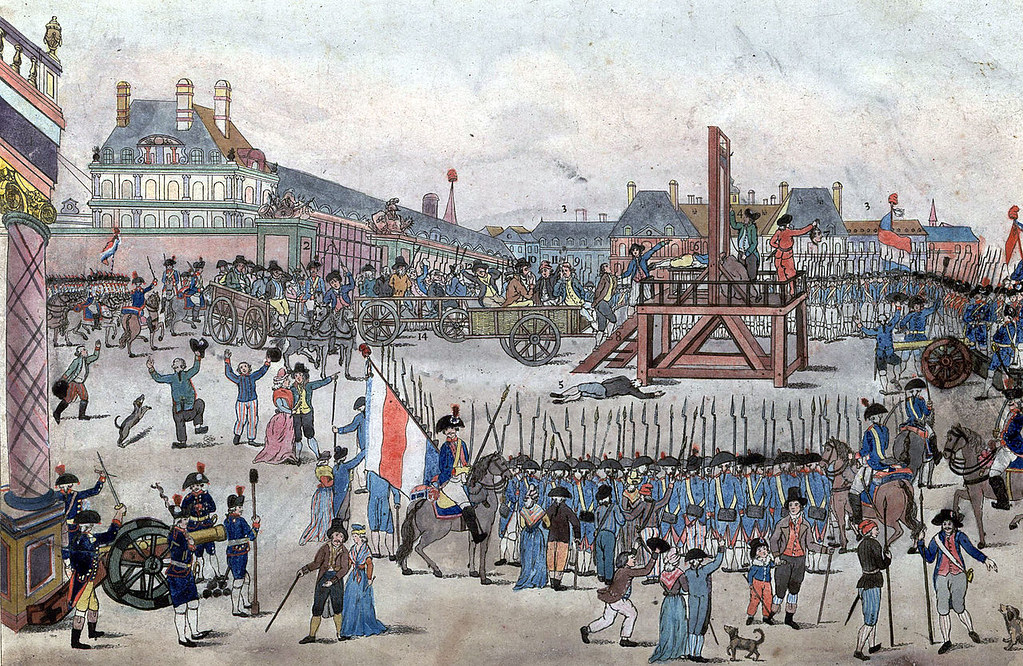

The Reign of Terror is a haunting and unforgettable chapter in the annals of the French Revolution; characterised by political radicalisation led by Maximillien Robespierre, it saw the relentless blade of the guillotine and the infamous executions of Marie Antoinette and Louis XVI. This tumultuous period prompts compelling questions about how the revolution transformed into its most radical and violent phase: was the Terror an inevitable consequence of royal betrayal and the increasing power of the people, or was it caused by an unfortunate deviation resulting from unforeseen circumstances?

Between 1789 and 1790, France was shattered by factional rivalries, suspicion, rampant fear, conspiracies, and denunciations. The outbreak of the Austro-Prussian War in 1792 added fuel to the smouldering fire of instability as France found itself facing formidable external threats. Louis XVI’s flight to Varennes in 1791 undermined the credibility of the constitutional monarchy, and his execution in 1793 signified a violent break from the old monarchical order, pushing the revolution beyond a point of no return. These unforeseen circumstances exacerbated existing social tensions, prompting the Jacobins to resort to radical measures to protect the revolution. However, attributing the roots of the Terror to circumstance is an oversimplification. The ideology of the revolution was key to shaping the Terror and its mouthpiece, Robespierre.

The Terror was an integral part of revolutionary ideology. The revolution was a radical break from the past. It strove for the perfect administrative and egalitarian society, henceforth everything – economy, society and politics – yielded to it. This democratic movement introduced personal, moral and intellectual problems to the public, and the Jacobins embodied this ideology in its most radical form. Robespierre’s 1794 essay On the Principles of Political Morality describes terror as “the only justice: prompt, severe and flexible”. The Jacobins sorted good and evil, truth and falsehood, into binary distinctions, justifying terror as the only way to safeguard the ideology of personal freedom. In this respect, it was a demand based on democratic political convictions and embodied the ideology of revolutionary activism. Robespierre believed that coercive force was necessary to form the new Republic and safeguard individual rights. In a sense, the Jacobin became an archetype of the revolutionist ideology.

Examining the Terror as a product of the revolution reveals that, no longer held together by the State, society recomposed itself in its most violent and radical form. The ideology of the Terror thrived on circumstance, becoming a possible, but not inevitable, outcome of the revolution.

By Sasha Braham